A MASTER AT WORK: ULRICH GERHARTZ INSTALLING UKARIA’S NEW STEINWAY D

INTERVIEW AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY DYLAN HENDERSON

THURSDAY 12 JANUARY 2023

Universally recognised as a piano whisperer, Ulrich Gerhartz is among a small handful of master piano technicians whose commitment to their craft and attention to detail is quietly astonishing. Employed since his apprenticeship in Steinway’s Hamburg factory in 1986, and currently Director of Concert and Artist Services at Steinway in London, Ulrich has completed the installation of new concert grands in many of the world’s finest venues, and serviced and prepared pianos for Alfred Brendel, Mitsuko Uchida, Evgeny Kissin, Imogen Cooper, Maria João Pires, Murray Perahia, and – of course – Paul Lewis. ‘In an all but invisible way,’ Jasper Rees wrote in a 2009 profile in the Guardian, ‘Gerhartz is probably the single most important figure in the entire piano world, at least to pianists and to concert halls.’

We were incredibly fortunate to have Ulrich ‘install’ our new

Steinway D-274 at UKARIA. On Thursday 12 January 2023, he spent over eight

hours regulating, voicing and tuning the new piano in the space to match

the unique acoustic of UKARIA. We are very grateful to Ulrich for

taking the time to answer a few questions.

Talk us through the main components of ‘installing’ a piano. What’s involved in that process, from start to finish?

‘It’s having the instrument in the acoustic of the hall, and seeing how the piano speaks to the hall, and adjusting the tone to get the perfect match between the individual piano and the acoustics. The reason why it’s taking a bit longer in this session, and the reason why I’m very happy to be here, is that when Paul [Lewis] and I selected the new piano, we actually selected one that wasn’t quite complete, because all the ones that were complete were not the right choice of instrument.

I really had to go into the details of setting the tone and working

on the hammers, from pre-voicing to final voicing, in order to get the

dynamic response that was correct for the hall. You can see from

watching me that you need a lot of patience, and it takes a long time,

because the piano is a very complex machine with 88 notes, with 88

hammers, and hundreds of mechanical parts that connect the key to the hammer, so

it is very involved.’

Did you do any work on the piano before it came here?

‘No – the last time I saw this piano with Paul was not even in the

selection room, but in quality control in the factory in Hamburg, when

it didn’t even have a lid. So I made a judgement on how to complete

the work. When you work on concert grands all the time, it’s almost

instinctive. You feel it almost as much as you hear it when you sit

behind the keyboard, whether the piano responds. Your work channels the energy

of the instrument as well, and that’s when it performs at its

best.’

Did you help Paul select it, or was it mainly his choice?

‘It was very much a team effort and when you work with great artists, it has to be a team effort. It’s not just the artist saying "I want this and this," because artists very often are not as informed about what goes into actually making a piano. So Paul was very glad that I was with him in the factory, and I was glad that I was in the factory with Paul! We were both scratching our heads after looking at the first eight pianos and thinking, “Oh my god, what are we going to do next?” Thankfully, I could pull some strings with my colleagues to make some more choices available, and that’s how we ended up with this piano.’

Tell us a little bit about your tools. What are they and what do they do?

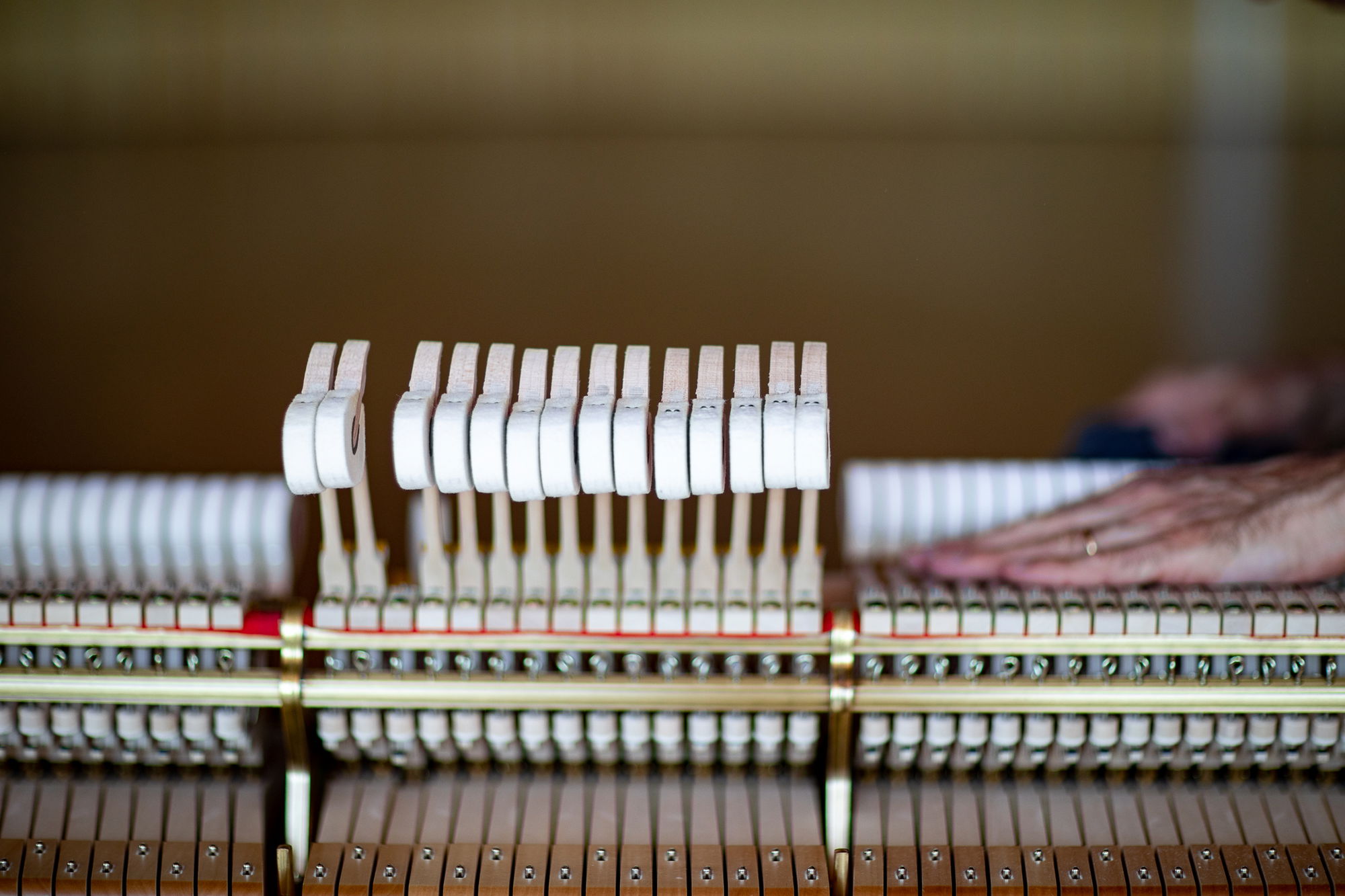

‘There are many different things one does to a piano. Usually when you’re introduced to a piano tuner, people think that they just tune the piano with a tuning lever: you make a few funny noises and then you walk away. But there’s many moving parts in a piano. The first stage in the setup of a new piano is to check the whole instrument to make sure that everything’s all right, that everything’s in place, that the hinges are OK, and that everything fits together. And for that you need normal cabinet-maker tools – screwdrivers, etc. Then when it comes to the mechanical regulation of the action, it is almost like surgical instruments or dentist’s tools: little hooks and screwdrivers and ratchets are used to make sure that, when the key goes down, the hammer reaches the string and at the right moment releases, checks up and repeats.

Then the next tools you have are the tools you need for tuning. I don’t use any electronic gadgets, just a tuning fork, some felt wedges to mute strings, and a tuning lever, which gives you access to the tuning pins. On a piano like you have here, there are 243 strings, and so you can get lost very easily if you don’t know what to do.

Then the final tools are those you use for voicing – they are the tools you saw me using today. They’re toning needles, which are literally like needles on a big handle. What I’ve been doing all throughout today is to change the elasticity within the hammers to get the right dynamic response. That is not just a little bit of pricking here and there, it’s incredibly involved. And that goes hand in hand with shaping. Once you’ve needled the hammer, of course it deforms, so shaping is needed to re-stablish the shape of the hammers. When you’re finished with this work, no one should ever know that any needle has touched the hammer. And for that you need sandpaper files of various different grades, and little hooks to take the hammer to the strings to make sure that every hammer hits the strings in a unison rather than it hitting one first and then the other two second, which would be a real problem for tone and for tuning.’

How do you actually make the tone brighter or darker?

‘By working on the elasticity – the hardness and softness – of the

felt on the hammers, and also by giving the hammer a certain shape. One

reason why a piano mightn’t sound good is if it’s played a lot, the

hammers might deform, and the strings might cut into the hammers, and

then it’s very difficult to have an elastic dynamic response, and it

will also be very difficult for the pianist to play pianissimo, because they can’t control (at very fine degrees) the attack of the hammer to the strings.’

How do you regulate the lightness and heaviness of the action? Is the touchweight fixed by the piano manufacturer, or do you have a huge amount of control over adjusting that to make it easier or harder to play?

‘The touchweight – the weighting of the keys – is done in production, or during a repair if you change hammers, you would then automatically need to adjust the weight. But that’s very involved work requiring a drill press and leads and all that sort of thing, so I would not expect to do that here, because that’s already been done in the factory. Heaviness or stiffness can also be caused by faults with the action. For example, if all the moving centres in an action are stiff or sluggish because of high humidity, then the action will become heavy and unresponsive. And that can be rectified by regulating, which would be a normal part of a service, and something that – if I come back – would be the first thing I’d check, to see if there’s any stiffness in the action. But you would not, unless you changed parts, start re-weighting keys in a service.’

What do you think of the relationship between the

Steinway D size and smaller acoustics like UKARIA? Were there any

refinements you needed to make to the instrument so that it would be

more suitable for this space?

‘That plays very much into the choice of the piano. In London I’ve got almost twelve concert grands that form my concert fleet, and they’re all selected as “personalities” to fit different venues. To give you an example, for the Royal Albert Hall for the BBC Proms, a 5,000-seat hall, you want a piano with a big, fast-projecting sound. In a hall like this, that’s the last thing that you need. Here, the piano sound comes slightly delayed, so it’s very suitable for accompaniment, for strings or voice, and it’s therefore very important that the piano doesn’t blast it all away. You want colour, and a certain kind of projection, but you don’t want a shouter of a sound in this hall.

It’s quite difficult sometimes for pianists when they’re used to

playing on bright pianos in big venues, and then they come into smaller

halls, where the pianos are voiced to fit the venue. Because the voicing

affects the way the action feels, and then they compensate and

over-project, because they don’t realise actually how loud the piano

sounds inside the hall. So it’s very important that someone listens to them, or someone plays the piano to the pianist so the

pianist hears the sound in the hall, and then usually they are

able to adjust their touch to find the right tone. Some pianists are

very good at playing in small halls, because they organically and

instinctively adjust their sound. They’re usually also the pianists who

can adjust very easily to different makes of pianos, and to different

ages of instruments, from fortepianos to modern pianos. But it’s a real

gift – not all pianists can do that.

How many new pianos like this do you prepare each year?

‘I probably set up new pianos in venues like this about three to

four times per year. I go to concert halls in the UK – usually in the bigger

cities – at least once a year for an annual service. The exception to

that would be if a VIP artist like Mitsuko Uchida, or András Schiff (or

Alfred Brendel in the past), would play in the venue, then very often I

would co-ordinate the service with the concert. In March, for example, Mitsuko Uchida is playing at St George's Bristol, so I have scheduled a two-day visit to service the resident pianos, finishing with her playing a perfectly set up piano at the end of the second day.'

I’m sure you’ve had many hundreds, but what’s been you’re most memorable collaboration with a pianist?

‘Yes, there’s many… Murray Perahia, Mitsuko Uchida, and Alfred Brendel, with whom I worked for well over twenty years. He was also Paul Lewis’s mentor, and my mentor in a completely different way: for Paul as a pianist and musician, for me, as a piano technician, to really understand what a pianist wants from a piano, and how a pianist listens. Brendel was very much listening to the piano like an orchestra – it had to be very well balanced, from the bass to the tenor, to the middle section, so you could hear all the different instruments within the piano. That’s exactly what this voicing process is like. How is this piano, as an orchestra, balanced between registers, and how many different colours can you create with it? The access for the pianist is through the keyboard – that’s the fascinating thing – and every pianist's touch and ear is different.

What I’m very proud of and what I really treasure are my recordings with Murray Perahia, because he’s the most amazing pianist and the most amazing recording artist. If I had to name one thing that I was really proud of, I’d say all the Bach recordings that Murray Perahia did between 2000 and 2016. They’re all done on pianos from London, whether the recordings were made in Switzerland or Germany or London, so that’s a great achievement. And then following that would definitely be all the years I spent with Brendel concertising and travelling.’

What’s the most challenging thing about your job?

‘The challenging thing is that one is a perfectionist. It’s not a job where you say, ‘I’ll do what I can and then I’ll go.’ One is highly sensitive to the effort that is made by people who buy a piano like this.

I will do what I can to make sure that they have the best possible piano, whilst creating a relationship that allows the venue to look after the instrument long term in an intelligent, cost-effective way, and allows the venue to protect the piano from being damaged due to poor handling by staff, and by piano technicians that are not so experienced on working on concert pianos all the time.

You have pianos in people’s homes that might be one hundred years old, and they are worked on by a piano technician. And then you have pianos like this that are more than a quarter of a million dollars and are like Formula One cars. You wouldn’t take your supercar to the local garage and ask if they could please tune the engine. It wouldn’t even occur to you.

It’s therefore very important for me to have a relationship with local technicians, so that there’s an understanding of what I do, and what they do, and how to work together, because they are necessary to look after the pianos on a day-to-day basis. In London it’s the same: I look after the pianos that are our own and the pianos that are in the main venues, but I work with a team of six tuners. Everybody communicates with everyone else. If someone tunes at The Wigmore Hall, and there’s a problem with the piano, I know about it that evening, and I can then ring Wigmore to say I need to come in and sort this out, whilst warning the next person who comes and tunes the piano that there might be an issue. And that allows us to actually provide the best service for venues.’